Grief, I thought, would be louder. A screaming kind of thing. A cinematic collapse on the floor, mascara running, fists pounding the earth. But when it came for me, it arrived like fog: slow, silent, and clinging to everything.

In February, I lost my mother.

That sentence still feels fictional. I write it and then reread it, as though the repetition might make it true. Or maybe untrue. I’m not sure which I want more.

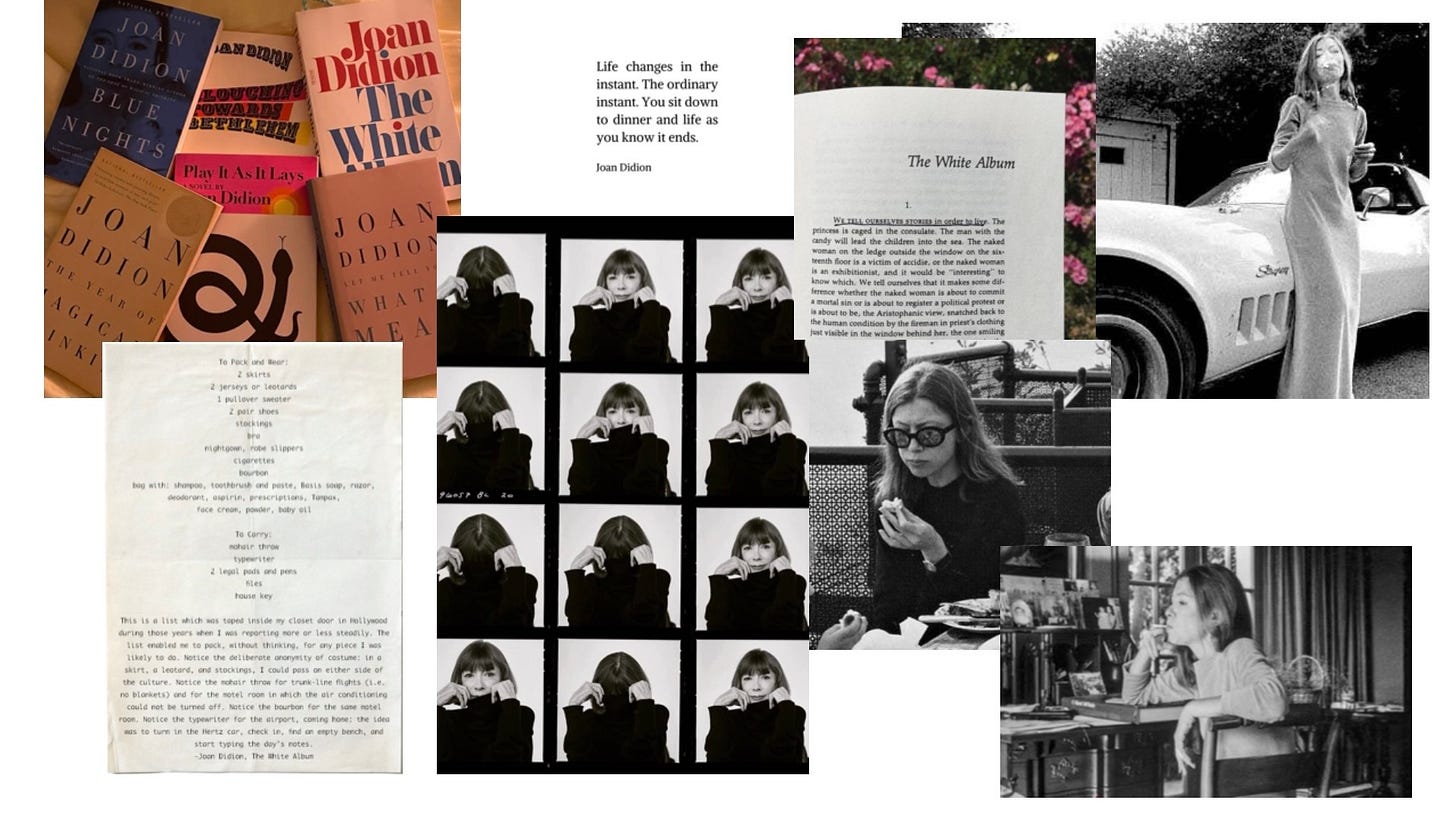

I didn’t have the words for any of it until I read The Year of Magical Thinking. Joan Didion did not scream either. She watched. She took notes. She wrote it down.

And in that quiet, I found my own grief staring back.

•

Didion’s grief isn’t clean. It loops. She insists, even while knowing better, that her husband might come back. That if she keeps his shoes, he will need them. That if she doesn’t say it out loud, it won’t be real. This wasn’t madness in the clinical sense—it was the mind trying to make unbearable things livable.

After my mother died, I became superstitious in strange ways. I clung to the mundane. Her scarf, still carrying the faint trace of her scent. I watched the same video of her on YouTube, singing buraanbur. I must have played it a hundred times. Her voice, strong and steady, became a thread back to something I didn’t want to lose. It felt like home.

I started speaking to her in my head—short thoughts, mundane updates, like she was just in another room. I told myself stories, because stories were all I had left. Didion writes: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” I told myself stories to survive.

And this is what she taught me: grief is a writer’s medium. Not because it’s beautiful (it isn’t), or profound (not always), but because writing is a way of organizing chaos. She gave form to the formless. Language to the unspeakable. I read her and felt permission—not to be okay, but to document the not-okay-ness.

•

I’ve always been drawn to women who look at the world slant. Who resist tidy narratives. Didion was slippery like that. California glamour, sharp intellect, deep melancholy. She didn’t perform strength, but she didn’t romanticize weakness either. She was just—there. Observing. Making a map out of her pain, even when it led her in circles.

There is something feminist, even radical, in her refusal to “move on.” In a world that asks us to grieve quietly, to return to work, to be productive in our pain, Didion lingers. She stays with the body. The absence. The impossible.

•

Reading her didn’t make me feel better. But it made me feel seen. And maybe that’s enough. Because mourning, like writing, is not about finding answers. It’s about bearing witness.

Joan Didion taught me that.

And I’m still learning.

for Mama

You were the first poem I ever heard.

Your voice still sings in the quiet corners of me.

Everything I write carries your rhythm.

I miss you in ways I don’t have language for yet—

but I’m trying.

This is for you.

This is incredible writing, Sakiya, so emotive, honest, & raw, & your poem at the end in honour of your Mother has moved me to tears. I am so sorry for your loss.💜

So beautiful ❤️. When I first started writing I could actually see grief as a fog that was filling my house… it’s a powerful thing. I’m sorry for your loss ❤️